Parts of a Sword and Their Anatomy Explained

Longer than a dagger and subtler than an ax, the

A

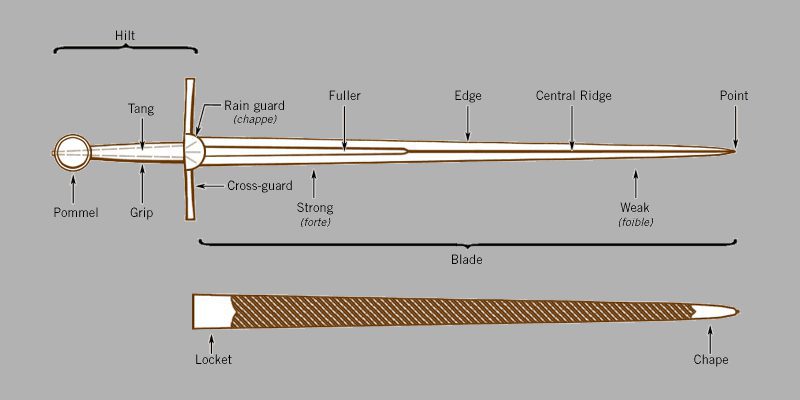

Hilt

The hilt consists of the pommel, grip, and

Pommel

Metal attached to the end of the grip, the pommel served as a counterweight to the blade, allowing a better hold on the weapon. Pommels were often spherical, but other shapes like triangular, mushroom, and brazil-nut were also common.

Grip

As the term suggests, the grip is the part of a

Sword Guard

The

On the other hand, the quillons are the arms of the crossguard on either side of the blade. Found in various shapes, they protected the wielder’s hand by blocking enemy blows. Some swords of the early 14th century had straight or forward-curving quillons.

Finger Guards

Sometimes called finger rings or arms of the hilt, the finger guards are the semi-circular bar at the plane of the blade attached to the crossguard. They protected the fingers gripping the ricasso and were common in thrusting swords like rapier and estoc.

Side Rings

Sometimes called ring guards, the side rings are positioned at the center of the crossguard, at right angles to the blade. They provided extra protection on the hand during parrying actions. They were common features on rapiers, two-handed swords, and the Scottish Lowland

Knuckle Guard

Sometimes called a knuckle bow, the knuckle guard is a narrow metal strip that curves over the length of the hilt, from the crossguard to the pommel. It laid the groundwork for the development of decorative hilts during the Renaissance. It protected the warrior’s knuckle, making it an essential feature on rapiers, smallswords, and sabres.

Basket Guard

The basket-hilted swords protected the wielder’s hand in a protective cage of metalwork. Basket-hilted swords were used throughout Europe from the mid-16th century, though they are often associated with the 18th-century Scottish broadswords. The Venetian broadsword or schiavona also features a distinctive form of basket hilt.

Blade

The blade is what makes a

Forte and Foible

The strongest part of the blade is called forte, from the French adjective fort, which means strong. It is located just above the hilt and may or may not be sharpened. On the other hand, the weakest part of the blade is called foible, from the Old French feble, which means feeble. It is located at the end of the

Edge

The edge is the sharpened part of the blade for cutting. Depending on the type of

Point

The point is the tip of the blade used for thrusting. In the Middle Ages, the development of plate armor required sharply pointed thrusting swords, with blades that taper more toward the point. However, other swords like the falchion are distinctive for their clipped tip.

Central Ridge

There are a great variety of sectional shapes in

Fuller

Sometimes called a blood groove, the fuller is a hollowed portion of the blade that runs along its length. It lightens the

Ricasso

Some European swords feature a ricasso, an unsharpened portion of the blade just above the hilt. It allowed the wielder to grip the blade safely past the

Scabbard

Scabbards often have a cloth lining to protect the blade and they are sometimes as expensive as the swords. Ancient swords like the Roman gladius had scabbards made from organic materials like wood and leather.

Early medieval scabbards were generally blocky, but they eventually became slimmer and more decorative in later periods. Viking swords and longswords had metal chapes that protected the end of the scabbard with later swords often featuring decorative metal fittings in silver and gold.

European Swords vs. Japanese Swords

European swords and Japanese swords have different constructions, and their

Japanese blades are also unique in the type of steel and tempering, as swordsmiths craft them from high carbon steel called tamahagane using traditional techniques. They also have several aesthetic features on the blade itself that make them a work of art, especially the hamon or temperline pattern. Still, both European and Japanese swords remain relevant in martial arts today.

Facts About the European Swords

In the Middle Ages, European swords started to evolve from the Viking swords into a classic cruciform design that we know today.

Here are the things you need to know about the European swords:

European swords varied in the type of steel and tempering.

The Romans used the piling technique on their gladius swords, while the Vikings utilized the pattern welding technique. The so-called Ulfberht swords had blades made of crucible steel, known as wootz and later as Damascus steel. Later improvements in

Blade designs adapted to fighting styles of the time.

Slashing swords such as those of the Viking Age, had blades efficient against lightly armored opponents. The development of heavy plate armor eventually led to swords efficient for thrusting. While cut-and-thrust swords had sharp edges and points, late medieval swords like estocs had an acutely pointed blade and served as armor piercers.

Some European swords had flame-shaped or flammard blades.

Many believe that a wavy undulating blade would inflict a more deadly wound than a straight blade. However, a flame-shaped or flammard blade made little difference in a

The curved blade was early appreciated in Asia before its introduction to Europe.

In Asia, the Persians and the Indians long used curved blades before the Turks introduced them to Europe. In the West, the Turkish scimitar was modified into the cavalry sabre. Japanese swords like the katana also relied on slightly curved blades with a two-handed grip and eventually became ornate weapons carried by the samurai class.

Medieval weapons remain relevant in Historical European Martial Arts.

Unlike modern fencing that grew from smallsword and military saber traditions, the HEMA focuses on fighting methods from classical antiquity, Late Middle Ages, and Renaissance. Practitioners often use the longsword, rapier, zweihander, and other medieval weapons. Some even study how to fight on horseback using the

Conclusion

Each type of